Research Paper

HOW DID THE FAME OF PHOTOGRAPHER NICK UT’S “THE TERROR OF WAR” CONTRIBUTE TO THE PRESENCE OF AMERICAN ANTI-WAR SENTIMENT THROUGHOUT THE VIETNAM WAR ERA?

Adelle Patten

Hum 104: Connections and Conflicts

Dr. Denham

May 7, 2018

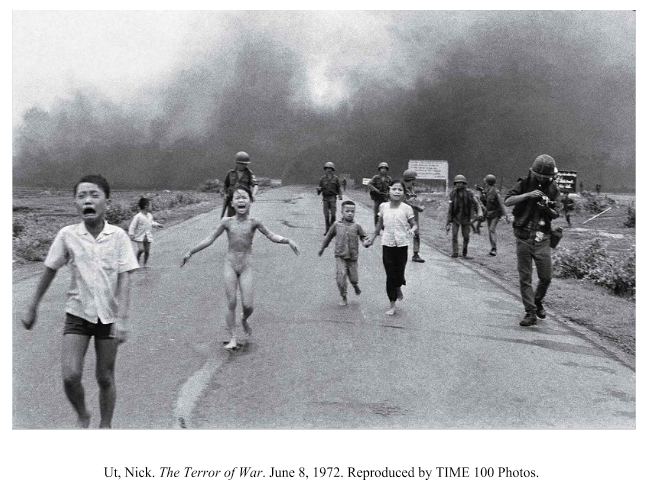

“The Terror of War,” otherwise known as “Accidental Napalm,” by Associated Press photographer Nick Ut, became an iconic image that possessed the power to sway American public opinion at the height of the Vietnam War by 1972. The image was captured on June 8, 1972, revealing horror as Vietnamese children run towards the camera, soldiers lagging behind, and with further distance, a dark, ominous cloud of smoke produced by napalm. The focal point becomes a naked young South Vietnamese girl, screaming in pain from napalm burns. Guy Westwill, author of Accidental Napalm Attack and Hegemonic Visions of America’s War in Vietnam summarizes the events leading up to Nick Ut’s photograph: “A battle was taking place between the South Vietnamese Army (ARVN) and the Viet Cong (NLF). As the news teams watched, South Vietnamese fighter planes flew overhead and dropped napalm canisters that missed the National Liberation Front (NLF) positions and exploded above a road on the outskirts of the hamlet. A few moments later a group of adults and children, some badly burnt, appeared through the oily smoke of the napalm explosion. As they ran, AP photographer, Hyung Cong “Nick” Ut, stepped into their path and took a photograph that would become one and the best known of the late twentieth century.” “The Terror of War” objectively evokes a wide range of emotions and ethical concerns to all viewers. Dissemination of what became infamously known as “Accidental Napalm,” contributed to the presence of strong American anti-war sentiment and fueled the pacifist movement that so heavily defined the Vietnam War Era.

Like visual art, photography enables viewers to participate in perceiving only “human” things, such as emotion. It is a universal language. However this language has limitations. While the beauty of photography is in its ability to communicate slivers of reality, and perhaps with more precision than paintings or text, this exclusively-photographic ability simultaneously presents its flaw. In Lights, Camera, War, Johanna Neuman discusses the impact of photography during the 1989 Chinese Tiananmen Square Massacre stating: “Images froze impressions, put weight on passing political movements, gave credence to fleeting truths, even lent themselves to manipulation for political ends. More, they had the potential to become the icons of national memory, a road map to collective emotion.” Her statement applies to all wars since the invention of the camera, but specifically to the Vietnam War and the repercussions of discourse around a few iconic images in America. Images such as “The Terror of War” share information regarding the climate of the Vietnam War the public would not have attained otherwise. Even the title of Ut’s image, “The Terror of War” insinuates the photograph’s “unveiling” of the Vietnam War realities and what was generalized to represent North Vietnamese civilian life.

As Susan Sontag discusses in On Photography, “Photographs may be more memorable than moving images, because they are a neat slice of time, not a flow…Photographs like the one that made the front page of most newspaper in the world in 1972- a naked South Vietnamese child just sprayed by American napalm, running down a highway toward the camera, her arms open, screaming with pain- probably did more to increase public revulsion against the war than a hundred hours of televised barbarities.” By reflecting on this one photograph and by validating the emergence of public revulsion, Sontag speaks to the photograph’s impact on Americans’ collective memory of the Vietnam War. Collective emotions mustered by “The Terror of War” form collective memories, and thus national identities based on historical events like the Vietnam War. Just as the iconic image of the Iwo Jima flag-raising continues to represent and associate patriotism with American participation in World War II, “The Terror of War” continues to harbor negative connotations today, even resentment, towards American involvement.

Distinguishing between public response to televised representations of the war and photographic representation of the Vietnam War, Sontag sheds light on “The Terror of War’s” power. It is due to the fame of explicit and controversial wartime photographs, that the American counterculture mobilized and that values largely shifted to pacifist ideals. As an iconic image, it captures one terrifying instance, one that both shaped public opinion of the Vietnam War and remains imprinted into the United States’ collective memory of the Vietnam War.

“Gatekeeping,” or the regulation of images to be published in compliance with institutional, commercial, and ideological standards, had a significant impact on the information shared publicly regarding the Vietnam War and American participation. A form of censorship and regulation by publishers including the Associated Press, the New York Times and NBC, gatekeeping aimed to stray from publishing photographs of body parts, dismemberment, evisceration, torture, and sexual violence. In fact, the iconic image of the “Accidental Napalm” has been cropped. The original image, viewed by the AP’s deputy photoeditor and declined due to full frontal nudity, included another photographer to the far right manipulating his camera. Despite the deputy photo-editor’s rejection, chief editor Horst Faas decided to overrule the former decision and it was sent to New York for publication. Editors and viewers alike debated over the aestheticization, desensitization and moral implications of this never-before-seen flagrancy of this image published by the Associated Press, The New York Times, and NBC. Its explicitness made it a highly-debatable image, serving as one cause of the controversy surrounding it.

“The Terror of War” made its way around the public sphere being used by other news sources, of which often manipulated its context by implementing captions, leaving messages and interpretations open-ended. For example, NBC may have contributed to the image’s nickname, “Accidental Napalm,” as they published it favorably, reading “Accidental napalm attack: South Vietnamese children and soldiers fleeing Trangbang on Route 1 after a South Vietnamese Skyraider dropped bomb. The girl at center has torn off burning clothes.’’ By using a defensive caption, NBC focused readers’ attention to the innocent intentions of the not American, but South Vietnamese Skyraider. NBC’s caption indicates the presence of war opposition and perhaps a general distaste by the American public towards news outlets. As Westwell argues,

The contextualization of the image here is consonant with the qualified reporting of the war in the early 1970s, during which time the mainstream media remained largely ‘‘on-side’’ with Nixon’s policy of ‘‘Vietnamization’’ (the heavy bombing of North Vietnam and Cambodia, and the shifting of the burden of fighting from U.S. to South Vietnamese troops) (Hallin, 1986, pp. 89).

Plainly stated, Hallin argues that 1970’s mainstream media tended to reinforce President Nixon’s goal of “Vietnamization,” or the efforts to gradually back out of war intervention, leaving most of the responsibility in the hands of South Vietnam. So, Westwell insinuates the influence of “The Terror of War” and goals of the American military intersected one another. By contextualizing the image, the public becomes more aware of the nation’s involvement. Looking at NBC’s caption of “Accidental Napalm,” the American public was also told who to blame for such visible horror, being the South Vietnamese military.

It is obvious what confusion a single image like “The Terror of War” can bring about, especially with the absence of a caption and differing ones. Similarly to today’s tendencies in the dissemination of news, truth and facts are difficult to come across. Solely sharing the image without a caption was not an option to mainstream news sources, but the image inevitably surfaced multiple reactions, in support and opposition of American involvement. It seems as though a portion of the public’s anger stemmed from conflicting information, in which one news source used the image to communicate a message, and another source, another message. Without accurate contextualization, it is easy to assume that the girl’s burns and utter pain were caused directly by the American military when in fact, it was the South Vietnamese military. One could imagine that America’s obsession with the image served as a catalyst for more inquiry and suspicion.

One accomplishment of iconic Vietnam War images was their ability to unite the public in their common civic duty as “spectator.” As Westwell discusses, Robert Hariman, professor of communication at Northwestern University, and John Louis Lucaites, professor of communication and culture at Indiana University, argue that the:

daily stream of photojournalistic images [. . .] defines the public through an act of common spectatorship’. The individual viewer can powerfully respond to an image, not as an individual but only as a member of the discursively organised public and as a part of a potential collective action in response to the image. Thus, in a culture dominated by images, the public would not be a public, and the individual, being powerful only within the framework and as a part of discursive-collective action, could not exert much political influence without viewing images – most of the time individually but, as a member of the public, at the same time also collectively.

In fact, it seems as though politics of the Vietnam War Era depended heavily upon iconic images and especially “The Terror of War” as it generated anti-war sentiment that fueled Vietnam War opposition. Further, the image influenced the political actions of President Nixon, his administration in its goal of “Vietnamization,” and the subsequent decisions of mainstream news. From this perspective, “The Terror of War” contributed, even defined, the pacifist movement’s iconography and solidified its association to American involvement in the war. Before the age of social media, this image emerged via television and by print, yet still possessed the ability to influence all aspects of the Vietnam War era from the acceptance of the stalemate, the unhonorable treatment of Vietnam War soldiers, and the methods of communicating information following its publication.

As Frank Möller argues in his publication The Looking/Not Looking Dilemma, he agrees with Patrick Hagopian, author of Vietnam War Photography as a Locus of Memory, in that “..photographs from the Vietnam War are said to have ‘brought home uncomfortable truths that people had long had reason to suspect, but which did not need to be confronted as long as they remained unproven…’” Thus, “The Terror of War” contributed to the validation of the American public’s suspicions. It visually and emotionally took its toll, solidifying understandings of what was perceived to be the nature of American intervention. By confirming such negative suspicions, Ut’s image provoked even more intense war opposition in 1972, nearing the end of American involvement in the Vietnam War a year later.

While I cannot conclude that “The Terror of War” single-handedly fueled the anti-war, pacifist movement of the Vietnam War Era, I can say it caused enough tension and lashback that Americans saw the end of American involvement in the war a year after its publication. My research, along with the claims and arguments of well-known historians including Susan Sontag, Frank Möller, Guy Westwill, Robert Hairman, and John Louis Lucaites, state that this image was one of only a few iconic images to determine public opinion and the actions of Nixon’s administration in their “Vietnamization” efforts following its publication.

After collecting research from scholars, one can reasonably conclude that “The Terror of War” did play a role in the formation of public revulsion by American involvement in the Vietnam War. But, I cannot know to what extent this image formed public opinion. Without knowing if it made its way on the AP wire, which media outlets published it, and how many, tracking its influence presents difficulty. To fully answer this question, “How did the fame of photographer Nick Ut’s ‘The Terror of War’ contribute to the presence of American anti-sentiment throughout the Vietnam War Era?” I would need to track the photograph’s dissemination through publications, speeches about it, and multiple opinions from those living through its publication. It would require an extensive amount of research that due to this project’s limitations, cannot answer. However, with this project, I can conclude by imagining “The Terror of War” intensified the leverage of the pacifist and anti-war movement based on historians’ claims.

Side note: The girl pictured in “The Terror of War,” Phan Thi Kim Phuc, sought medical attention immediately after the photograph was captured by photographer, Nick Ut. Later, he also helped her move to Canada.

Bibliography

Hariman, Robert, and John Louis Lucaites. “Public Identity and Collective Memory in U.s. Iconic Photography: The Image of “accidental Napalm”.” Critical Studies in Media Communication 20, no. 1 (2003): 35-66.

Möller, Frank. “The Looking/not Looking Dilemma.” Review of International Studies 35, no. 4 (2009): 781-94. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40588074.

Neuman, Johanna. Lights, Camera, War : Is Media Technology Driving International Politics. 1st Ed. ed. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1996.

Sontag, Susan. Essays of the 1960s & 70s. Edited by David Rieff. New York, NY: Library of America, 2013.

Ut, Nick. “”The Terror of War”.” Digital image. 100 Photos. Accessed April 26, 2018. http://100photos.time.com/photos/nick-ut-terror-war.

Westwell, Guy. “Accidental Napalm Attack and Hegemonic Visions of America’s War in Vietnam.” Critical Studies in Media Communication 28, no. 5 (2011): 407-23. doi:10.1080/15295036.2011.577790.